When the International Monetary Fund (IMF) sounded its latest alarm, it was not over global trade tensions or inflation in the developed world; it was over Africa’s own balance sheets. The Fund’s October 2025 Regional Economic Outlook for Sub-Saharan Africa, released during its Annual Meetings with the World Bank in Washington, paints a picture both resilient and risky. The report shows that while the continent continues to “hold steady” with a projected 4.1 percent growth in 2025, governments are paying more to borrow at home than abroad, tightening fiscal space and deepening a cycle of domestic financial dependence.

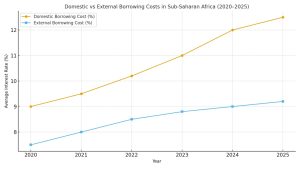

The domestic cost of capital remains elevated across the region, the IMF declared, warning that this surge in local borrowing is “significantly more expensive than external borrowing” in many countries. The reliance on domestic banks to plug fiscal deficits is crowding out private-sector lending, raising financing costs, and trapping commercial banks in a web of sovereign exposure that threatens both government solvency and banking stability.

READ ALSO: Strengthening Fiscal Sovereignty: African Countries with Low IMF Debt Levels

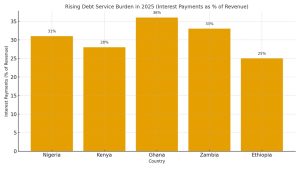

For many African treasuries, the shift to domestic borrowing was meant to shield them from the volatility of global credit markets and foreign exchange pressures. Instead, it has become an expensive safety net. According to the IMF, sovereign bond yields in the region average above 12 percent, nearly double pre-pandemic levels, while the spread between local and foreign borrowing has widened sharply. In Nigeria and Kenya, interest payments now consume nearly one-third of government revenues, limiting their ability to fund development projects.

Between 2019 and 2024, domestic banks’ holdings of government debt across the region grew faster than in any other part of the world, creating a dangerous bank–sovereign nexus. When governments borrow heavily from local banks, their fiscal vulnerability becomes a systemic risk to financial stability. If a government defaults or delays repayment, the impact spreads directly into the banking sector, weakening capital buffers, constraining credit to the private sector, and triggering liquidity strains that reverberate through the broader economy.

The IMF cautions that this “vicious feedback loop” is tightening faster in Sub-Saharan Africa than elsewhere. In countries where the government already dominates the financial system, such as Ghana, Nigeria, and Zambia, the crowding out of private credit is limiting small-business growth and pushing up the cost of loans to households and entrepreneurs.

Africa’s resilience has defied expectations, but the external landscape remains punishing. Global growth, according to the IMF’s World Economic Outlook, is expected to slow by 0.2 percentage points in 2025–26. Commodity prices have been uneven: oil continues its decline amid weak global demand, while cocoa, coffee, and gold prices remain elevated, benefiting exporters such as Côte d’Ivoire and Ethiopia.

External financing conditions have improved slightly since April, as the US dollar weakened and some emerging-market central banks resumed monetary easing. Yet sovereign spreads remain elevated, and many African nations face rollover risks on debt repayments due in 2025–26, amounting to $2.3 billion for Nigeria and $2.9 billion for South Africa. The IMF’s data also shows that 20 countries are now either in or at high risk of debt distress.

Meanwhile, the global aid environment is deteriorating. The OECD projects a 16–28 percent fall in bilateral aid to Sub-Saharan Africa this year, equivalent to nearly 1.5 percent of regional income. Fragile states such as South Sudan, the Central African Republic, and Niger could lose over 10 percent of their government revenue from aid reductions, endangering healthcare, education, and humanitarian programmes.

When Fiscal Fire Meets Monetary Ice

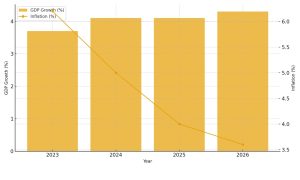

African governments now walk a tightrope between inflation control and debt servicing. Median inflation has declined to about 4 percent in 2025, down from over 6 percent in 2023, reflecting lower food and energy prices. But inflation remains in double digits in one-fifth of the region, including Angola, Ethiopia, Ghana, and Nigeria, where volatile exchange rates and imported inflation persist.

This dual challenge, tight fiscal space and high domestic rates, leaves policymakers with little room to manoeuvre. Raising interest rates to contain inflation further increases debt-servicing costs, while easing those risks capital flight and currency depreciation. The IMF notes that in about half of the countries with double-digit inflation, interest-to-revenue ratios exceed 20 percent, deepening tensions between fiscal and monetary policy.

The region’s foreign reserves also remain thin. One-third of Sub-Saharan African countries hold less than the recommended three months of import cover, and for low-income economies, the median reserve level is down to 2.5 months, reflecting interventions to stabilise currencies under pressure.

When Debt Crowds Out Growth

Africa’s fiscal fragility is not just a matter of numbers; it is a question of lost opportunity. Rising debt service costs are crowding out investments in essential sectors. The IMF’s findings reveal that development spending in infrastructure, health, and education has declined steadily since 2020, as interest obligations soak up scarce revenues.

In many cases, the pivot to domestic borrowing has merely shifted rather than solved the debt problem. With local bond yields above 14 percent in some economies, governments face growing pressure to sustain domestic investor confidence through higher returns, which in turn drive inflationary expectations and currency depreciation. This loop—debt, interest, inflation, becomes a recurring cycle that drains fiscal energy and stifles productive investment.

The IMF warns that the resilience seen in headline growth figures masks deep structural fragilities. The region’s average per capita income growth remains below 1 percent, meaning millions of Africans are still growing poorer in real terms despite aggregate GDP expansion.

The IMF’s Prescription: Reform and Revenue

In its policy recommendations, the IMF underscores two major imperatives: domestic revenue mobilisation and strengthened debt management. The former is not new, African governments have long been urged to broaden their tax bases but the IMF’s 2025 report presents fresh data. Across Sub-Saharan Africa, the median tax-to-GDP ratio is around 15 percent, compared to over 25 percent in advanced economies. Closing even part of that gap could yield billions in annual revenue.

The IMF points to success stories: Rwanda’s adoption of digital tax platforms, Ghana’s e-VAT initiative, and Togo’s integrated tax and customs administration have collectively boosted compliance and reduced leakages. In Rwanda, the shift to electronic filing and real-time invoicing has lifted taxpayer participation by over 40 percent and raised revenue efficiency. Ghana’s phased e-VAT rollout has increased collections among large taxpayers by more than 50 percent since 2023.

On debt management, the Fund highlights Benin’s fiscal transparency reforms and Côte d’Ivoire’s debt-for-education swap (2024) as promising models. By publishing comprehensive debt data and improving investor communication, Benin has successfully lowered its borrowing costs and extended maturities. The IMF and World Bank’s 2024 Joint Domestic Resource Mobilisation Initiative and the G20 Framework for Debt Transparency (2025) both aim to scale such reforms across the continent.

Home-Grown Reform Must Be the New Fiscal Compass

Yet, as sound as these recommendations are, the continent cannot indefinitely operate under externally driven frameworks. The IMF itself acknowledges that success hinges on “strong ownership of reforms and deft handling of political economy.” African nations must therefore evolve from compliance to authorship, crafting fiscal policies that reflect not only global standards but continental priorities.

A home-grown fiscal strategy must anchor itself in four principles: domestic credibility, regional integration, innovation in capital markets, and inclusive growth. The first requires transparent budgetary processes and credible macroeconomic anchors. The second calls for aligning debt management with the financial integration goals of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), a potential game-changer for intra-African capital flows. The third demands the development of regional bond markets and sovereign wealth platforms that pool risks and reduce dependence on volatile foreign finance. The fourth, perhaps most vital, is to ensure fiscal frameworks serve people, not just balance sheets.

A Fiscal Renaissance, Not a Rescue Mission

The IMF’s message is clear: resilience is not recovery, and stability is not sustainability. But Africa’s future must not be confined to the boundaries of multilateral caution. The continent’s economies, dynamic, youthful, and inventive, must turn the present warning into a renaissance of fiscal autonomy.

A new African fiscal framework should blend prudence with purpose, building institutions that can both attract capital and allocate it equitably. It should view debt not as a trap but as a tool for development, channelled through transparent, high-impact investments in green energy, digital infrastructure, and human capital. Initiatives like the African Development Bank’s Domestic Bond Market Initiative and emerging blended finance models in Nigeria, Senegal, and Tanzania provide proof that Africa can lead its own solutions.

If the IMF has sounded the alarm, Africa must respond not with panic but with purpose. The path to fiscal freedom will be neither short nor simple, but it is necessary. For too long, the continent’s fiscal compass has pointed outward. It is time it pointed home.