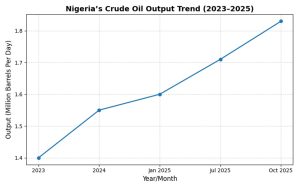

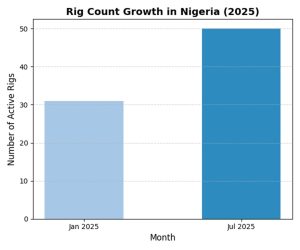

Nigeria’s renewed oil ambitions are beginning to bear fruit. Under the government’s “Project One Million Barrels” (1MMBOPD) initiative, crude oil output has climbed to between 1.7 and 1.83 million barrels per day (bpd) as of October 2025, the country’s highest consistent performance in nearly three years. Rig activity, a key measure of upstream confidence, has surged from 31 in January to 50 rigs by July 2025, a growth rate unmatched in the sub-Saharan region.

This resurgence is the product of a sweeping policy reset anchored in the Petroleum Industry Act (PIA) of 2021, a suite of presidential executive orders, and the hands-on coordination of the Nigerian Upstream Petroleum Regulatory Commission (NUPRC). Together, these reforms are reshaping the sector’s landscape, cutting costs, unlocking investment, and aiming to restore investor trust that waned during years of volatility and policy uncertainty.

READ ALSO: Nigeria at 65: Jarrett Tenebe’s Call for Unity, Renewal, and Progress

Yet, as promising as these numbers appear, the ultimate test lies not in output spikes but in consistency. Can the reforms that now power Nigeria’s production also sustain it and make the country a trusted, predictable destination for global capital?

The Petroleum Industry Act (PIA) was the most significant restructuring of Nigeria’s oil laws in decades. Enacted in 2021 after nearly 20 years of legislative inertia, it dismantled the opaque bureaucracy of the old Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC) and birthed a commercial entity, NNPC Limited, designed to operate competitively in global markets.

Beyond that, the Act created the NUPRC as the technical and commercial regulator for the upstream segment, tasked with driving efficiency, transparency, and investor confidence. By 2025, the Commission had issued 25 key regulations and incorporated 137 Host Community Development Trusts (HCDTs) to strengthen relations with oil-producing communities and prevent production disruptions, according to Upstream Gaze Magazine Vol. 8.

Under its Regulatory Action Plan (RAP), NUPRC set an ambitious goal, to reduce Nigeria’s average upstream production cost to below $20 per barrel, a target that, if achieved, could bring the country closer to the operational efficiency of peers such as Saudi Arabia and the UAE. It also prioritised the Domestic Crude Supply Obligation (DCSO), ensuring local refineries like Dangote and Port Harcourt have access to feedstock, thereby boosting domestic refining and reducing import dependency.

The government complemented these regulatory efforts with executive orders aimed at shortening contracting timelines from 38 months to 135 days and cutting the industry’s 40% cost premium, as confirmed by the President’s energy adviser, Olu Verheijen, at the 2024 African Energy Week in Cape Town.

Signals of Recovery

The progress of these reforms is visible in the country’s production data. According to the NUPRC’s official July 2025 production report, Nigeria’s liquid hydrocarbon output rose to an average of 1.71 million bpd, comprising 1.507 million bpd of crude oil and 204,864 bpd of condensates. This represented a 9.9 percent year-on-year increase from the 1.56 million bpd recorded in July 2024. Month-on-month, production improved by 0.89 percent compared to June 2025’s 1.69 million bpd.

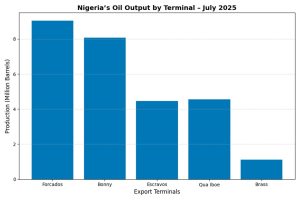

Terminal-level figures underscore the momentum. The Forcados terminal led with 9.04 million barrels in July, up from 8.85 million barrels in June, while the Bonny terminal jumped by 12.7 percent to 8.07 million barrels. The Escravos terminal expanded by 7.1 percent to 4.47 million barrels, and the Brass terminal saw the steepest rise, a 27 percent increase to 1.12 million barrels. Only the Qua Iboe terminal recorded a slight drop to 4.55 million barrels, reflecting temporary maintenance activities.

This pattern reveals more than short-term gains. It signals that reform is beginning to penetrate deep into infrastructure nodes and operational frameworks, leading to efficiency improvements across both onshore and offshore assets.

Investment momentum is returning. Various reports suggest that major international oil companies (IOCs) such as ExxonMobil, TotalEnergies, and Shell have either renewed commitments or divested assets to capable local firms, unlocking over $5.5 billion in indigenous-led investment. TotalEnergies’ new deepwater Production Sharing Contract (PSC), signed in September 2025, marks the country’s first major offshore investment in over a decade, reflecting growing investor confidence under the PIA regime.

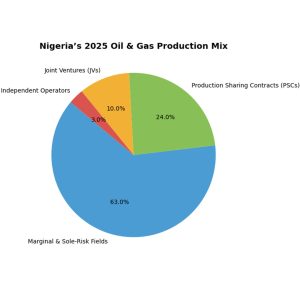

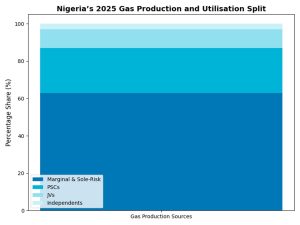

The gas sector, too, is witnessing renewed activity. Nigeria’s average daily gas production reached 7.59 billion standard cubic feet in mid-2025, a significant increase from previous years, accompanied by a drop in gas flaring to a three-year low of 7.16%, with 63% of output now coming from marginal and sole-risk fields, according to NUPRC data. The Nigerian Gas Flare Commercialisation Programme (NGFCP), a key element of the energy transition, has already auctioned 49 flare sites, targeting the capture of 250 million cubic feet of gas per day, potentially reducing annual emissions by six million tonnes of CO₂.

These achievements speak to a coordinated, reform-driven momentum that Nigeria has long sought but rarely sustained.

The Test of Sustained Output

The challenge, however, is that reforms must translate into resilience. While the Upstream Gaze report celebrates the NUPRC’s bold strategy and “cost-efficiency renaissance,” it also warns that sustaining gains requires vigilance in security and governance. Oil theft, sabotage, and vandalism, long the Achilles’ heel of Nigeria’s petroleum sector, continue to erode potential output.

In 2024, the government launched Operation Delta Sanity to curb theft and restore production in the Niger Delta. Though successful in recovering several illegal connections, production losses from sabotage and downtime still account for roughly 100,000 barrels per day, based on NUPRC field data.

Labour and infrastructure disruptions also persist. In September 2025, a brief strike at the Dangote refinery cut national crude output by nearly 16%, highlighting the fragility of Nigeria’s operational ecosystem. Midstream bottlenecks, including recurring leaks and vandalism on the Trans-Niger and Trans-Forcados pipelines, remain barriers to seamless exports.

Moreover, while the PIA’s 30% frontier exploration fund encourages new discoveries, critics argue it diverts revenue from national and subnational accounts, potentially straining fiscal balances.

In essence, Nigeria’s oil revival, though substantial, still rests on fragile ground, one where policy execution, not policy design, will determine longevity.

A Global Lens

Globally, Nigeria’s production rebound positions it more competitively within OPEC, especially as countries like Angola and Equatorial Guinea face output declines. Yet, to cement investor confidence, Nigeria must navigate a world steadily tilting towards energy transition and decarbonisation.

The NUPRC’s introduction of a Carbon Credit Policy and its collaboration with Infosys to automate hydrocarbon accounting signal that Nigeria is thinking ahead. If effectively implemented, carbon trading could generate a new revenue stream and reposition Nigeria as an energy producer aligned with global environmental benchmarks.

However, as Upstream Gaze cautions, the global investment climate is evolving. Financial institutions are tightening green mandates, making ESG compliance a determinant of future funding. Nigeria’s ability to meet environmental and social standards under the PIA’s Sections 102–103 on environmental management and Sections 232–233 on decommissioning will therefore play a crucial role in sustaining foreign direct investment.

Investor Trust and the Road Ahead

Trust, in the end, is Nigeria’s most valuable export. The PIA and its implementing agencies have begun to rebuild it, but global investors remain watchful for consistency. The reforms have cut bureaucracy, stimulated capital inflow, and strengthened community participation, but the world will measure success not by declarations, but by delivery.

If the government can maintain regulatory predictability, enhance infrastructure security, and achieve its sub-$20 production cost goal, Nigeria could once again command the confidence of global oil investors. And if it channels a share of its hydrocarbon revenues into renewable projects, it could redefine itself not merely as an oil exporter, but as a 21st-century energy hub balancing production with sustainability.

Project One Million Barrels, therefore, is not just about scaling output. It is a litmus test of Nigeria’s capacity to combine reform, efficiency, and credibility in equal measure. In the volatile theatre of global oil markets, consistency is the new currency, and for Nigeria, sustaining trust may prove even more valuable than hitting a million barrels a day.